“At school they give you shit, drop you in the pit,

You try, you try, you try to get out, but you can’t because they’ve fucked you about”.

(Crass-Do They Owe Us A Living)

Once more on the ‘memory-go-round’ dear friends, once more. Another trip back in time to when we were much younger, more naive, less jaded and cynical, more hopeful. Where every new musical movement, event or scene that presented itself to us, seemed to offer up new possibilities that would perhaps catapult us into adulthood. The promise of a new found knowledge and education, less formal than school, but oh so important!!!

I remember running home from town that Saturday morning, with THAT record tightly tucked under my arm. The rush of anticipation to get back and play THAT record was almost overwhelming, so much so that I had completely forgotten the usual Saturday routine of avoiding particular streets, and keeping a keen eye out for the skinheads that would revel in the oft opportunity to beat the crap out of a 14 year old punk in town on his own. Such was the excitement, it shattered my Saturday ritual of going to my favourite record shop, Vinyl Demand, where I would usually hang out all day, with my mates listening to the latest punk releases, reading zines and talking about the next gig or latest release or band. So as you can gather this was most unusual behaviour for me, but this was a most unusual record; a record of mammoth proportions that promised everything I needed at that point in my life, and didn’t fail to deliver. Actually that last bit is not quite true, but almost delivered everything and set me on a trajectory that has ingrained itself in my lifecourse.

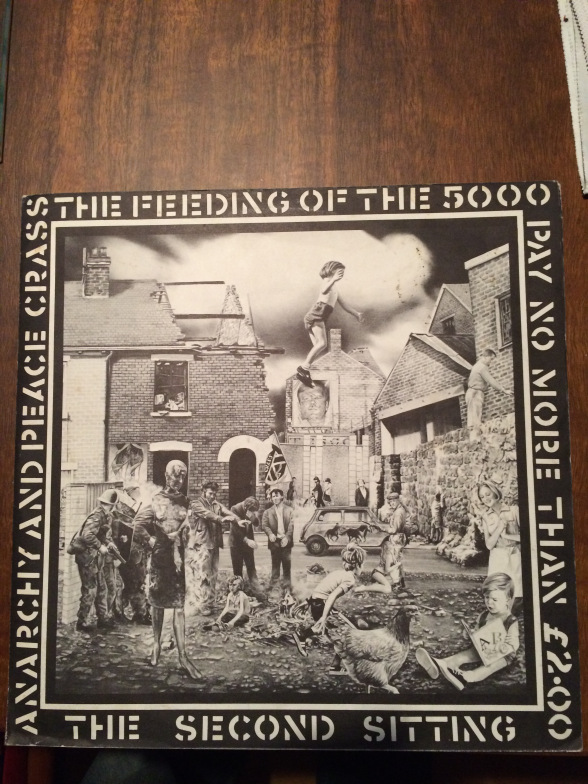

I was familiar with the band Crass through fanzine articles and I had heard on the grapevine and through the punk ‘zines about this record, edgy, dangerous, controversial, blasphemous, lots of swearing; everything a good punk record should contain. I had reserved a copy of ‘Feeding of the 5000’ for its release date based on a recommendation from Terry, owner of Vinyl Demand, spitting image of Phineas Freak and a throwback to the hippy 70’s counter-culture; and now once collected, after waiting for him to open the shop that morning, was on it’s way back to my bedroom where my record player awaited.

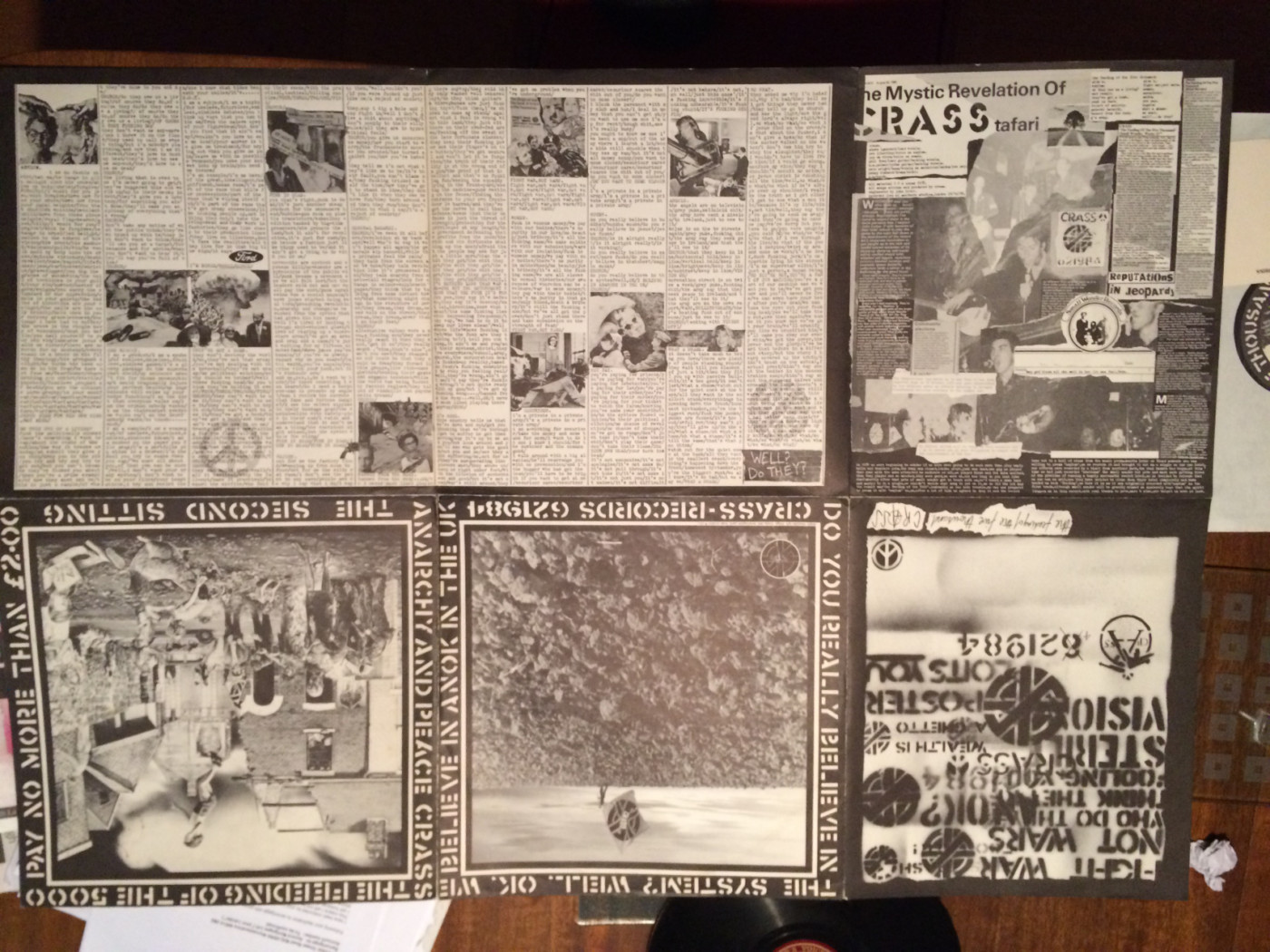

So I finally got home, panting, out of breath but very, very excited. I carefully slipped the vinyl out of the gatefold sleeve in anticipation, placed it on my record player dropped the needle into the lead in groove, turned it up full volume and waited. I played that record consecutively probably about 15 times, over and over that day, and to be frank I thought the music wasn’t all that great. It wasn’t the punk I was used to listening to but that seemed to pale into insignificance because what that record taught me was a perspective that I was never going to get taught at school. The one great thing about Crass and their records was the aesthetic of the record sleeve, and this sort of set a template for many anarcho-punk records that followed in its wake. The sleeve unfolded into 6 sections to a disturbing and shocking poster of a dismembered hand impaled on barbed wire with the ironic war recruitment cry ‘Your Country Needs You’.

Alongside the images of war, animal experimentation, state violence were treatises and two line statements, questioning power, authority and encouraging self autonomy and dissent. But most importantly were the LYRICS. This was raw truth, an exposition, an explanation and I am not exaggerating when I say that record changed my life, it articulated everything I was feeling at that time as a 14 year old punk. How school, your parents, your teachers, the police were all colluding against you to try and control your life or at worst fuck it up, to turn you into a subservient robotic worker. Get qualifications, get a job, get married, get a house and become a slave to the system. Of course those weren’t the words I was using at that particular point; but that moment, that vinyl epiphany, suddenly started to put vague threads of thoughts, feelings and ideas into place; into some semblance of cohesive order and importance. The combination of stark imagery, and powerful words were like gold dust to a young boy trying to find his place in all this madness of youth.

So as you can see those lyrics were so important in my education, my politicization and the values and beliefs I developed and gained from my engagement with anarcho-punk have, in most parts, remained with me though in a less naive and Utopian way as I have got older and more measured. Part of my research is to explore if, and how, my research participant’s engagement with anarcho-punk as adolescents has had a lasting impact on their subsequent adult lives. Going through the data of my research interviews the issue of the importance of the lyrics of anarcho-punk songs kept coming up in those discussions. I am going to share with you some of those discussions along with the ‘The Feeding of the 5000’ for your aural enjoyment

The early roots of it to me was simply that experience probably related to Crass, I guess, I mean my memories of sitting there unfolding Feeding of the Five Thousand and listening to Crass and there was an expectation that you sit there and you’d read through the lyrics and you’d look at images and that would have been alongside the fairly bouncy music. And you would punctuate that music with your own reflection on what that lyric was about and reference that more broadly, I was more conscious of that. Less so than what I refer to as the 1st wave of Punk but Anarcho Punk that seemed to be the template to me, that was set out by Crass for me in that way. Cut up artwork and a focus on lyrics that were normally shouted and quite abrasive music with a punchy rhythm which was the anarcho-punk construct really. And that formed an attitude within myself that was my expectation of what stimulated me, what was relevant, what was real. (S)

The first anarcho-punk record I heard was probably Feeding of the Five Thousand, which I didn’t really enjoy that much at the time. The person who played it at me was obviously very excited about it and showed me the pictures, and read the words out to me and this I found more interesting than the actual music, which I thought was badly produced and recorded. The music was fairly irrelevant to me – it was the politics which was of much more interest. Of course there was a political slant to songs by The Clash and others, but I guess that really didn’t strike a chord with me. Whereas the lyrics of the anarcho-bands were much more clearly defined as protest songs which highlighted the problems within the “system” and offered solutions. (G)

I did have a key moment reading Crass lyrics at a skate park in Kettering which a friend brought along and something struck me about it. It was saying things that I’d perceived and it was expressing how I felt about my position in life. I was 14 /15 and the lyrics were articulating how I was feeling. Obviously things are a lot more kind of amorphous and vague, you’re listening to different stuff and influenced by different things and it’s not just one moment or not just one thing particularly. (M)

I just went Wow. I had to listen to the whole double album twice because I thought it was so brilliant and I really, really liked it a lot. It spoke to me. The words, the lyrics, the anti- religion stuff, the anti-war stuff, the anti-rich stuff, the anti-class stuff, it encapsulated what I was thinking at that time which they put into song……when the Anarcho Punk bands came along they were actually saying something. Conflict, animal rights that kind of stuff and that was more me, you know. I think music’s important and it can change people, it changed me, it changed my perception of things, it educated me (W)

Somebody somewhere played me a Crass song and I just thought, “I want some of that”, and I can’t even remember what song it was, but yeah. So I went out and hunted down ‘Feeding of the 5000’. It was just unlike anything I’d heard and it was so obviously angry and, you know, I couldn’t understand a bloody word of it. So I thought if I go and buy it and listen to it I might understand what the hell they are saying, apart from the ‘fuck, fuck, fuck’, you know. Which is weird, because now I listen to ‘Feeding the 5000’ and I can understand everything he says. . I mean the lyrics of the songs either helped me at the time cus I was so fucking angry with nowhere to place the anger and….they shaped me politically, so I channelled that anger and developed my own thoughts. They made me think a lot, you know. I went out and read stuff that I would never have read if it hadn’t of been for that, you know. Stuff on animal rights for example, and 31 years later I am still a vegan, about the only one out of all the people I used to know. (C D)

Crass’ Penis Envy is quite a significant album. Erm….. a strong feminist thing, female adolescence. I mean I don’t know if I completely understood everything that was going on. And then things change as well. The music of Vi Subversa, Poison Girls, I mean I loved that stuff, oh, I suppose that’s quite significant actually. Poison in a Pretty Pill, I was struggling with the contraceptive pill when I was 19 perhaps and er…I hated it and it was just like, for fucks sake, messing about with my body. And I played Poison in a Pretty Pill and burnt my contraception pills at the same time, that’s quite a significant one!. Poison Girls, I actually understand the lyrics these days, where I don’t think I really did back then. Because I was a teenager, I was just a bit of a kid, Vi Subversa was talking about a mutual women’s life and so I look at those song in a completely different perspective now. (J M)

Crass ‘Feeding of the 5000’ was actually the first time I’d read the lyrics to a punk song as well. It came out with, it came with a booklet inside with all the songs in the booklet so I sat there every night reading the booklet. I’m sure if you talk about Signs and Receivers and everything I’m sure the lyrics were just as important. Obviously the music came first to the receiver ……all these ideas and concepts were certainly being implanted which otherwise wouldn’t have happened if it was without the lyrics booklet. I also remember prior to that, in terms of lyrics, you know, you’d get Smash Hits, you’d cut out the lyrics to punk songs and stick them on your wall and stuff. But you never really, I was never aware of sitting down and listening to the lyrics to you know, UK Subs, ‘Strangle Hold’, while listening to the record the way that you would with Crass records. The lyrics were kind of like an afterthought. The lyrics didn’t really count until Crass. The simple fact that if you were to listen to the record you wouldn’t have been able to make out a fucking word Steve Ignorant was singing so you needed the lyric sheets with the record to be able to follow them. (C L)

Because I came from a poor background, my family is so poor and have always struggled, possibly from that side of things, you know. Crass were singing about my family, the way I’ve been brought up as fodder, respecting Queen and country or you supposed to and it just struck a chord with me. When you bought the records you had the lyrics with it, didn’t ya. I read ‘em, read ‘em and read ‘em. I’d put the record on the record player and I’d play it over and over till I got to know all the lyrics. Not only that with the Crass records you’d have so much information on the sleeve, I’d read it, I didn’t understand all of it but I’d read it over and over again to learn and understand more. It was an education, it was more of an education than what you were getting at school really cus I wasn’t interested in getting educated at school and …. I had such a big interest in anarcho-punk. That was my education (C)

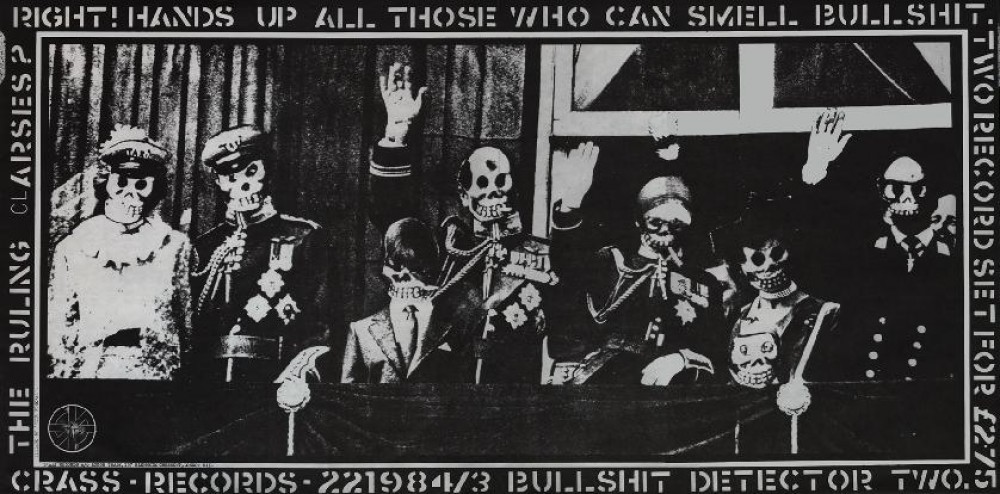

The lyric sheet/booklet and accompanying imagery played an important role in the propagation and circulation of some of the core ideas in anarcho-punk. I mentioned earlier, that seminal Crass recording and visual aesthetic set a template within anarcho-punk where the record sleeves started to take on a similar role to the fanzines and political and ideological treatises that were circulating within that scene. The record sleeve became more than just a carrier of the artefact, the record, but a carrier of ideas, politics, protestations, ideologies, values and beliefs that were implicit to the development and reinforcement of anarcho-punk. They were also implicit in my own personal and political development, opening up new possibilities, somewhere to direct my anger and frustration, giving me strength and hope; a reason……….